Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap

AC/DC

The band had a kind of hunger in 1976 that sounds like a fist on a table. AC/DC arrived at Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap already bruised and sharpening. They had released two Australia-only studio albums, High Voltage and T.N.T., and then an international High Voltage compilation in 1976. They were road-tested. They were a five-piece that had learned to play together under pressure. Bon Scott sang like someone who had seen too much and kept smiling. Angus and Malcolm Young were already defining a guitar shorthand of stop-start riffs and single-note venom. The record that followed those early records would have to hold the band’s live threat while making the songs into hooks that could travel.

The center of gravity for the record was at Albert Studios in Sydney under the steady hands of two older men. Producers Harry Vanda and George Young were ex–Easybeats who had become house producers at Albert Productions. They understood how to turn a raw electric band into a record that still snapped. George was also the elder brother of Angus and Malcolm. That family connection was not sentimental. It was practical. George and Harry had a studio vocabulary and a discipline the Young brothers accepted. What they wanted from AC/DC was body, groove, and a mean sense of humor. They got all three.

The world outside the studio looked volatile and small at the same time. In 1976 rock was fragmenting into careful prog on one side and punk on the other. AC/DC refused both. Their music owed more to Chuck Berry and to the hoarse blues tradition than to any fashion. The band leaned into black humor and petty criminality. The title phrase came from a cartoon character, Dishonest John in Beany and Cecil, and became a concept: stories of petty revenge, small-time sin, sexual boast, and loneliness. Bon Scott’s lyric voice is both confessional and performative. He could be comic. He could be cruel. He could be sorrowful. That range would give the album its character.

They were not finished with questions about how they should break into the wider world. Atlantic in the United States watched them with suspicion. The band toured the UK in early 1976 but had visa problems and uneven label support. The songs on this album were written and road-hardened in a band that still believed the only proof of music was the audience’s roar. The record was both a calling card and a briefcase of tools. It offered jokes, slow sorrows, and a soundtrack for getting even. It wanted a stage and it wanted trouble. It got both.

The sessions began and ended under the roof of Albert Studios in Sydney. Recording took place in patches from late 1975 into 1976. Most tracks were cut in December 1975 through March 1976 at Albert Studios. A later track intended for an international edition, "Love at First Feel," was recorded at The Vineyard, London, in September 1976. The process was stop-and-go. Touring squeezed the calendar. That urgency left marks on the record.

Production came from the duo known as Vanda & Young: Harry Vanda and George Young. They had produced AC/DC’s earlier work and they kept the band in a narrow, live-focused frame. They did not over-layer. They favored punch, presence, and a slightly dry room sound. Their engineering choices emphasized Bon Scott’s midrange vocal and the interplay between Angus’s lead stabs and Malcolm’s rhythm. The result is a record that sounds like a band in a small club, recorded with confidence and without studio fuss.

The instruments are plain and decisive. Angus’s Gibson SG–style attack is up front. Malcolm’s Telecaster-like chunk sits just behind it. Mark Evans plays bass throughout. Phil Rudd supplies drumming that favors pulse over flash. The production kept the drum sound tight and present, not cavernous. The guitars were tracked to tape using the room as amplification. The record’s distortion comes from players and amps rather than excessive studio processing. You can hear finger noise, string slides, and the occasional scrape of a cymbal. That texture matters.

There were small studio decisions that shaped the record’s character. On the Australian sequencing George Young is credited with playing bass on the third track, which gives that cut a slightly different bottom end. Two songs were lengthened or shortened between the Australian and international releases. The international mix trims the title chant and tightens endings on a couple of tracks. These are editorial choices meant to make the songs punchier for overseas radio. The original Australian LP leaves room for longer grooves and a looser cadence.

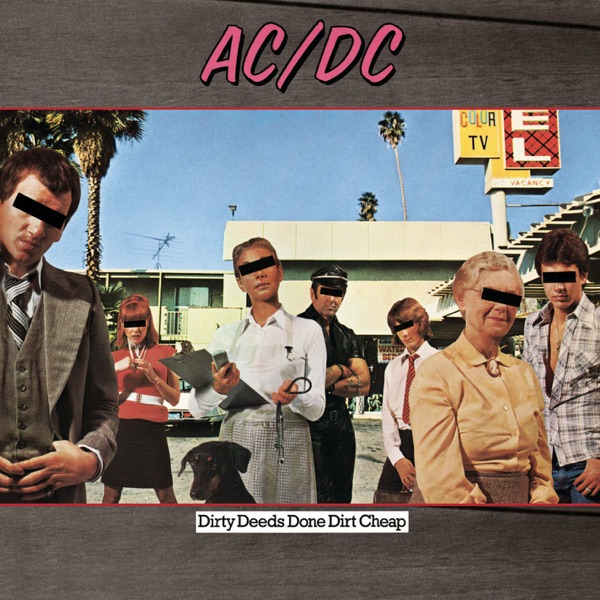

Cover and sleeve choices were part of the album’s presentation. The Australian sleeve was assembled by Richard Ford at EMI Studios, Sydney. The international image was remade by Hipgnosis, showing a motel tableau that doubled as menace and comic tableau. The photos and the music work the same angle. They offer small crimes, small jokes, and a sense that the world you are hearing is slightly out of joint.

Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap The title track is theater and threat in three minutes. Bon Scott narrates like a small-time operator with a business card. The refrain of the phone number, 36-24-36, is a concrete image that makes the song vivid and dangerous. Musically it is compact. Angus’s opening figure clamps the groove. Malcolm’s rhythm is telegraphed and unrelenting. The chant at the end was shortened for the international release, but the Australian version keeps the full, menacing repetition. The song sets the album’s moral ground: humor, menace, and a speaker who offers services at a discount. It is the record’s center and its billboard.

Ain't No Fun (Waiting 'Round to Be a Millionaire) This is a sly, extended stomper that lets the band stretch its blues vocabulary. Bon’s vocals slide between boasting and weary sarcasm. The track is among the longest on the album in its Australian form and that length allows the band to stretch the groove and to include on-the-edge shouting and an explicit fade with a profanity that refuses to be decorous. The song is part-world-weary monologue and part-riff sermon. It works as a character study of the hustler who will not wait for luck.

There's Gonna Be Some Rockin' This cut is pure rock and roll propulsion. It borrows the rhythm feel of older Chicago blues and early rock in a way that makes the song feel both retro and immediate. George Young is credited with bass on this track in the Australian sequencing. That substitution gives the bottom a tightness that pulls Angus’s licks forward. The lyrics promise action rather than philosophy. Placed early, it keeps the momentum after the longer second track and reminds listeners why AC/DC were first and last a live band.

Problem Child A live favorite and a straightforward hard rock manifesto. The riff is built to be shouted back at Bon. He would introduce it in concert as being about Angus, which is more joke than confession. The guitar arrangement reserves space for Angus’s exuberant solos while Malcolm keeps the timing precise. The song’s narrative is a compact portrait of adolescent antagonism. It functions as a release valve. After a few songs of menace and swagger the album needs a pure, unrepentant roar. This provides it.

Squealer This track is rough in subject and rougher in tone. Bon described it in interviews as a narrative about a sexual encounter, and the vocal performance is coarse and direct. Musically the band leans into a heavier blues-rock posture. The guitars are gritty and the arrangement allows for a heavy midsection that underscores Bon’s storytelling. Placed as the opener of side two on the Australian pressing it returns the listener to the album’s seedier half.

Big Balls A comic set piece with precise musical delivery. On its face it is a bawdy joke with double meanings, but the arrangement is immaculate. A syncopated piano-like figure in the rhythm guitar and a clean vocal approach on the verses give the song a vaudeville sneer. Its placement pegs the album’s sense of humor. International editions faded the track differently, but the joke remains. It shows the band’s willingness to play with persona and to allow Bon’s wink to be part of the record’s propulsion.

R.I.P. (Rock in Peace) A short, sharp rocker that appears on the Australian edition and was later replaced on the international release. It plays like a B-side elevated to album status. The guitars are lean and the lyric is a compressed, sardonic meditation on fame and mortality. It functions as a palate cleanser before the album’s slowest, most surprising moment. In sequence it keeps the record from becoming a single-minded parade of riffs.

Ride On The album’s single moment of open sorrow. Bon’s voice is low and conversational. The song is a slow blues, and the performance reads like confession. The lyrics speak of regret and of wasted chances while the guitar solo by Angus is patient and elegiac. Placing this song late on the record gives it weight. It could have been a throwaway in any other catalogue. In this one it becomes a hinge. It proves the band could do feeling without apology.

Jailbreak A cinematic close for the Australian sequence. The story is literal and noir. Bon opens scenes and details as if he is giving stage directions. The riff is muscular and the arrangement is cinematic without being indulgent. Released as a single before the album in June 1976, the song became a staple of the band’s live set. As a final track it leaves the listener outside the cell, hearing the band’s speed and its taste for melodrama. It is both an exclamation point and a hand reaching out.

The album works as a sequence because it balances three tones. It alternates threat and joke, and then it inserts a slow moment of truth near the end. The Australian sequencing favors longer grooves and a grittier arc than the international variant. Side one opens with the title’s promise and then pushes through swagger and fury. Side two deepens into sleaze, laughs, and finally regret. The editors who shortened songs for the international market tightened the record for radio, but they also clipped some of its patience. The Australian version breathes more. It asks to be heard as a set of characters moving through similar streets. Each track is a different room in the same house. The arc ends not with triumph but with escape. That is the album’s honesty.

The reception at first was regional and uneven. Released in Australia on 20 September 1976 by Albert Productions, the record made clear headway in the band’s home market. The modified international edition followed later in 1976 for the UK and Europe. In the United States Atlantic hesitated and initially declined to release the album. The band’s profile in America would arrive later with Highway to Hell and then explode with Back in Black.

Commercial fortunes changed after the band became a global phenomenon. After the success of Back in Black and the renewed interest in AC/DC, the US division of Atlantic authorized an American release of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap in March 1981. The record then reached the top five on the Billboard 200, peaking at number three. In Australia it had previously peaked inside the top ten on the Kent Music Report, reaching number five. The delayed American release turned the record into both a rediscovered artifact and a commercial windfall.

Critics and fans found different reasons to love the record. Some praised its lean riffs and Bon Scott’s mercurial voice. Others objected to its crude humor and lyrical roughness. Over time the album’s roughness became part of its reputation. Songs like "Ride On" and the title track emerged as the emotional and theatrical centers of the record. The album’s combination of comic nastiness and a small, aching blues made it a talking point for listeners who wanted rock to be both direct and a little dangerous.

The cultural imprint widened as the band’s legend grew. The title phrase entered popular currency and the title track became one of AC/DC’s signature numbers. The record influenced hard rock acts that favored rawness over polish and taught bands how to carry humor inside menace without losing credibility. It also fed into a broader appetite for rock that prioritized rhythm and immediacy. The album’s delayed American release, and its subsequent chart success there, complicated the band’s chronology in the US but cemented its international stature.

There were legal echoes of the record’s concreteness. After the US release a lawsuit was filed by a family who alleged their number had been inadvertently included in the song’s refrain and that prank calls had followed. That suit is a small, literal testament to how precisely a lyric can land in the world. The album kept both its swagger and a practical consequence. It made noise. It made money. It made trouble.

Today the album is read as a turning point. It captures a band still rough at the edges but finding formal invention in repetition. It records Bon Scott at his most cunning and most vulnerable. It preserves a young hard rock band learning to do character work inside three-chord architecture. The songs keep being played, covered, and argued about for what they reveal rather than for any tidy moral. The record’s voice remains immediate because it was made by players who refused to hide how they sounded.

SOURCES

- Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap - Wikipedia article (detailed album page)

- "Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap" (song) - Wikipedia

- AC/DC Official Website "On This Day 1981" (release and chart notes)

- Vanda & Young - Wikipedia (biography of producers Harry Vanda and George Young)

- George Young (rock musician) - Wikipedia

- Murray Engleheart and Arnaud Durieux, AC/DC: Maximum Rock N Roll (biography, 2006)

- Mick Wall, AC/DC: Hell Ain't a Bad Place to Be (biography)

- Connolly & Company discography entry for AC/DC "Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap" (release dates and catalogue information)

- Discogs entries for various releases of Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (pressing and release details)

- Apple Music album page for Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap (release date listing)

- Classic Rock Review, "Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap by AC/DC" (analysis and context)