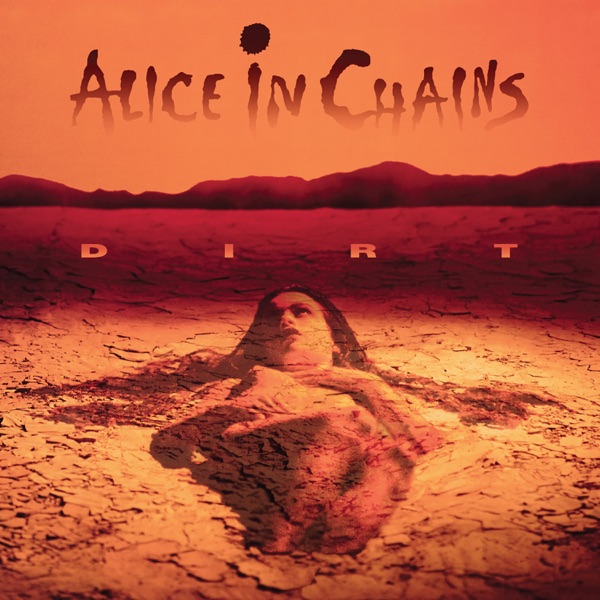

Dirt (Remastered)

Alice In Chains

September 29, 1992 came after a year the band had already made the country notice them. After the 1990 release of Facelift and the acoustic detour of the Sap EP in February 1992, Alice In Chains had moved from regional hard rock hopefuls into a band whose sound threaded metal density through Pacific Northwest melancholy. The session that produced the song "Would?" for the Singles soundtrack in the spring of 1992 acted as a hinge. It brought the group into a broader cultural conversation and left them poised at a crossroads between the heavy and the intimate.

The band entered the sessions with demons that were no secret. Layne Staley had checked out of rehab and then reportedly relapsed. Sean Kinney and Mike Starr were also struggling with substance and alcohol issues while Jerry Cantrell carried the bulk of the songwriting. The record the quartet set out to make was written mostly on the road and in the margins of tours. The songs that became Dirt were built out of that friction. The lyrics name addiction, death, broken relationships, and anger. They do not moralize. They record the state of being inside those things.

Recording began in the spring of 1992 at studios in three cities: Eldorado (Burbank), London Bridge (Seattle), and One on One (Los Angeles). The sessions opened in April as the nation watched the verdict in the Rodney King case. The Los Angeles riots began on April 29, 1992. The band was in or around Los Angeles when the unrest broke out. They paused. They fled with guest Tom Araya from Slayer to the Joshua Tree desert for a few days. The riots left a reportable imprint on the record. The music remembers the sensation of watching fire on a television screen and then stepping outside to a different kind of noise.

The material itself arrived as a newly concentrated Alice In Chains. Jerry Cantrell supplied most of the songs. For the first time Layne Staley wrote songs of his own that also featured him on guitar, notably "Hate to Feel" and "Angry Chair". The band wanted to make something heavier and darker than Facelift while still threading in melody and harmony. The result was a record that took the compact, crushing riffs of metal and the introspective, acoustic heart of Seattle's scene and welded them together. The aim was not to invent a new sound. The aim was to stare. The album would force listeners to look back.

Dave Jerden returned as producer after working with the band on Facelift. He and the band recorded between April and July 1992 across three studios to capture different textures and to work around schedules and mood. Jerden’s role was practical and tonal. He returned to coax a heavier, thicker guitar sound and to keep the vocal performances raw and immediate.

Jerden’s technical approach became central to the record’s sonic identity. He reportedly blended multiple amps for Jerry Cantrell’s rhythm guitars to get low, mid, and high frequency definition. Accounts attribute a combination that included a Bogner Fish preamp for low end, a Bogner Ecstasy for mids, and a Rockman unit for the top end, with close miking on cabinets and DI for the Rockman channels. The band double tracked and layered guitars extensively. The result is a guitar tone that is both saturated and clear. It allows Cantrell’s harmonized leads to sit above a molten, compressed bed of rhythm.

The personnel in the room were the four original members: Layne Staley on vocals and occasional rhythm guitar, Jerry Cantrell on guitars and co-lead vocals, Mike Starr on bass, and Sean Kinney on drums. Additional hands appear as anecdotes rather than full features. Tom Araya is said to have been in the studio and contributed the vocal for the short interlude known as "Iron Gland". The track "Would?" had been recorded earlier with producer Rick Parashar for the Singles soundtrack and was brought into the album. Engineers on the project included Bryan Carlstrom and Annette Cisneros, and Ulrich Wild also worked on engineering duties. The mixing and mastering choices favored presence and weight. Vocals were often left forward and unvarnished. Guitars were compressed, wide, and dense. Drums were immediate and clipped to the point of impact.

The atmosphere in the studios was shaped by more than gear. There are widely reported accounts that Staley was using again during the sessions and that Jerden and others clashed over attempts to get him sober. The band took breaks. They moved between London Bridge, where the Pacific Northwest’s room sound and familiarity tightened performances, and the Los Angeles and Burbank rooms, where different consoles and monitors generated different mixes of aggression and detail. What the tapes preserved is not a polish. It is the edge of a band in acute focus and in private collapse. That contradiction is audibly central to the record.

Them Bones The album opens with a two-and-a-half-minute strike. Jerry Cantrell wrote the song about mortality and fear of death, and the music matches the subject. The riff is chromatic and tightly coiled and the verses sit in an odd meter that many transcribers identify as 7/8 before the chorus snaps into 4/4. Layne Staley’s voice screams like a hand being pulled from a hot surface and then settles into choruses sung as if in confession. Production compresses everything so the song lands hard and leaves no air. As an opener it announces the record’s priorities: blunt force, uneasy structure, and a lyric that refuses platitudes.

Dam That River This is a propulsive blast of anger and impatience written by Cantrell. The rhythm is a bulldozing chug that pushes Staley’s voice into snarls and near-speech. The title image is hydraulic and violent. In interviews Cantrell has tied the song to personal squabbles inside the band. The production places the bass and kick forward to keep the song piston-like. Sequenced here it follows "Them Bones" as a second strike and keeps the momentum tight while widening the emotional palette from existential dread to interpersonal rage.

Rain When I Die This is one of the longer tracks on the record and it bears introspective songwriting. The lyrics were shaped by Cantrell and Staley around relationships and the strain of living on the road. The arrangement opens space for Cantrell’s quieter moments and then folds back into heavier refrains. The guitar layers breathe a little more here. Staley’s chorus lines sit over a low, rolling bed of bass and tumbling cymbals. Placed third, the song functions as a textural broadening. It gives the listener a different set of consequences to the album’s central habits of danger and surrender.

Down in a Hole Written by Jerry Cantrell and sung in duet with Layne Staley on co-lead lines, this is the record’s portrait of isolation. The arrangement is built around a minor-key progression that allows Cantrell’s arpeggiated acoustic and electric lines to weave with Staley’s aching timbre. The song moved quickly in listeners’ ears to become one of the album’s most tender and direct statements. It also demonstrates the band’s ability to shift into a near-ballad without losing the album’s weight. The studio left the vocal intimate and brittle. The listener feels the room.

Sickman This track was conceived after Staley reportedly asked Cantrell for the heaviest and sickest thing he could write. The result is a murky, menacing slow burner that examines the interior collapse of someone who has traded pain for numbness. Cantrell’s guitar work is both murk and menace. The production keeps the bass fuzzy and close, and Staley’s vocal slides into a half-whisper at moments that magnify threat. In the album sequence it begins the second act of songs that take addiction as subject and plot.

Rooster This song is Jerry Cantrell’s tribute to his father, Jerry Cantrell Sr., and to the scars left by the Vietnam War. The title comes from his father’s nickname. The guitar work is less staccato than on the opening tracks. The arrangement stretches into a slow, deliberate march with harmonized vocals that make grief into testimony. The music video filled in the song’s autobiography by including Cantrell’s father in footage that matched the song’s narrative. On the record it functions as the album’s moral center. It shows a way of turning trauma into recognition rather than into spectacle.

Junkhead Here the album slides into autobiography of the addict. The title says what the song will explore. Musically it is taut and angular and the lyrics carry the voice of someone for whom the drug habit has become identity. Cantrell and Staley place imagery of hunger and exchange in short, sharp lines. Production choices keep things claustrophobic. The listener should hear the echoing smallness of rooms where deals are made and then nightmares follow. It sits in the sequence as the beginning of the album’s narrative descent.

Dirt The title track is one of the blacker entries on the record. Staley wrote the words to a melody that Cantrell had given him. The lyric reads like accusation and confession. Musically the song opens a wide, droning space and then tightens into riffs that grind. The production makes the guitars thick and sedimentary, like layers of earth compressing over time. As the record’s namesake it does the essential work of naming the album’s soil: a place where pain is planted and roots choke.

God Smack This is raw and nasty and specific. The title can mislead. It does not mean a punch from a deity. It is one of the songs that directly addresses heroin. Cantrell and Staley use claustrophobic images and a relentless riff to suggest the way the drug narrows perception and flattens consequence. The chorus is forceful. The guitars are saturated. In the sequence it is one of the darker nodes, an emphatic statement of the album’s concerns.

Iron Gland A short, 40- to 45-second interlude, often unlisted on some pressings, that began as a riff Cantrell played to annoy the other members. The band turned it into a joke track. Tom Araya of Slayer reportedly supplied a guttural vocal exclamation for the line made famous by the interlude. The effect is comic and curt. Placed where it appears it can feel like a pressure valve. It is brief enough to be dismissed, but its presence also registers the band’s capacity for black humor even amid the record’s seriousness.

Hate to Feel Written by Layne Staley and featuring him on rhythm guitar, this is one of the most intimate confessions about heroin’s hold. The vocal delivery is at times fragmented and at times incandescent. Cantrell’s guitars circle and close in. The studio treatment leaves Staley’s voice up front with a grainy coloration that sounds like someone shouting from inside a bottle. In the arc of the album it is the moment when the interior experience of use is made clear and almost unbearable.

Angry Chair Also written by Layne Staley, and one of the few songs on the record where his hand can be heard on both lyric and guitar. The song begins with a slow, ominous recoil and then opens into a chorus with a hook that is almost perversely singable. The lyrics name dependence and the loss of control, but the arrangement gives those themes a strange, aching tenderness. Studio performance is raw. The vocal is close. The guitar solo moves like an argument with melody.

Would? Originally recorded for the Singles soundtrack with Rick Parashar and then placed as the album’s closer, "Would?" is Jerry Cantrell’s tribute to the late Andrew Wood of Mother Love Bone and a question of consequence and action. Cantrell sings the verses and Staley answers on the choruses. The arrangement rides a slow, grinding groove with a bass and drum pattern that undergirds the vocal dialog. The song’s placement at the end sends the record out with insistence rather than closure. It leaves the question hanging. It asks the listener to decide whether any of the album’s violence can be named or redeemed.

The album’s sequencing moves like a confined novel. It opens with immediate shock and then widens into scenes of personal memory and addiction. Side one of the original CD and vinyl places the more direct, riff-driven tracks first to batter the listener’s defenses. Side two becomes a descent, groupings of songs that focus the theme of heroin and its consequences into a small narrative arc with "Junkhead", "Dirt", "God Smack", "Hate to Feel", and "Angry Chair" placed to tell a story of escalation and then of attempted recognition. The brief oddity "Iron Gland" acts as a nervous laugh in the middle of that arc. Ending with "Would?" returns the record to a public square. The band refuses closure. The last line asks a moral question rather than giving one.

Dirt arrived on September 29, 1992, into a world that had already been listening for the darker harmonies of Seattle. It reached No. 6 on the Billboard 200 and remained on the chart for an extended run. The record was certified multi-platinum in the United States and internationally, and it became the band’s biggest seller. Its singles such as "Would?", "Them Bones", "Angry Chair", "Rooster", and "Down in a Hole" all received radio play and video rotation.

Critics took note. The record was nominated at the 1993 Grammy Awards in the category Best Hard Rock Performance. Publications that followed guitarists and heavy music praised the album’s sonic architecture and Cantrell’s guitar voice. Others focused on Staley’s frightening immediacy. The album was not just reviewed. It became an artifact for conversations about addiction and the costs of fame. The MTV Video Music Awards acknowledged "Would?" as Best Video from a Film in 1993 for its appearance on the Singles soundtrack and its visual framing of the song.

The album’s cultural footprint expanded during the 1990s and beyond. It is regularly cited in retrospective lists that mark the best work to come out of that era. Rolling Stone and other publications have placed it on lists of essential grunge and metal albums. By the 21st century the record had accrued the status of a touchstone for musicians who wanted to marry heavy riffing with melodic hooks and lyrical candor about self-destruction. Bands in metal and alternative scenes have acknowledged its influence on tone, arrangement, and on placing confessional lyrics in a hard-rock format.

The legacy is not uncomplicated. The album was the band’s last made with bassist Mike Starr, who was dismissed the following January during the supporting tour. Layne Staley’s own decline continued in public life and then ended with his death in 2002. The record is therefore freighted. It is listened to now both as music and as document. It still pulls. That pull is not nostalgia. It is recognition of what the music recorded and what the lives around it revealed.

SOURCES

- Dirt (Alice in Chains album) - Wikipedia entry (detailed recording, personnel, release and chart performance)

- "Would?" - Wikipedia entry and Singles soundtrack notes (production by Rick Parashar; MTV VMA award)

- History.com - "Los Angeles Riots" (April 29, 1992) overview and timeline

- Guitar World - interviews and features on Jerry Cantrell and Dave Jerden's production approach

- Revolver magazine interview/feature referencing Tom Araya's studio cameo

- David de Sola, Alice In Chains: The Untold Story (Thomas Dunne Books, 2015) - contextual biography and interview material

- Jake Brown, Alice in Chains: In the Studio (collection of session details and technical notes)

- Billboard chart histories and RIAA certification database (commercial performance)

- Rolling Stone lists and features on grunge and metal (retrospective rankings)

- Liner notes from Music Bank box set (1999) and official reissue materials (notes on songwriting credits and session details)

- Interviews and archived magazine pieces: RIP Magazine (1993), Kerrang!, and press coverage from 1992–1994 (contemporary reviews and reportage)